Our History

1920s: FOUNDING OF THE ASSOCIATION

On January 6, 1920 in New York City, A.L. Viles, the General Manager of the Rubber Association of America (RAA, later named the Rubber Manufacturers Association (RMA), and today’s U.S. Tire Manufacturers Association (USTMA)), welcomed a delegation of twelve rubber manufacturers from Canada in the RAA offices. The Canadian delegation included Ames Holden Tire Company, Canadian Consolidated Rubber Co., Dunlop Tire & Rubber Goods Co. Ltd., Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company of Canada Ltd., Gutta Percha & Rubber Ltd., Independent Rubber Co., Miner Rubber Company, and Partridge Rubber Company.

Following discussion on topics of interests to the both Canadian manufacturers and RAA members, the delegation and RAA unanimously concluded that an effort should be made to form an organization among firms of the rubber industry in Canada which could be affiliated with the Rubber Association of America under conditions to be later determined. To this end, a committee was struck to arrange a general meeting in Canada for which the matter might be further discussed to secure definite action. The committee consisted of:

Messrs. A.D. Thornton Canadian Consolidated Rubber Co.

W.H. Miner Miner Rubber Company

C.N. Candee Gutta Percha & Rubber Ltd.

C.H. Carlisle Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company of Canada Ltd.

At this point in history, the Canadian organization was thought of as a Section of the RAA. It was agreed that RAA’s A.L. Viles will attend this subsequent meeting and A.D. Thornton, as a current member of the RAA, will endeavor to interest other Canadian firms who are not yet members of the RAA to apply for membership as a prior condition to their joining the Canadian section when it is formed.

On February 4, 1920, a group of interested Canadian rubber manufacturers and A.L. Viles held a meeting at Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company of Canada Ltd. in Toronto, and discussed the forming of a Canadian Section of the Rubber Association of America Inc. By acclamation, C.H. Carlisle was elected Chairman pro tem.

At that meeting, A.L. Viles presented RAA’s latest Annual Report, described the nature of the work undertaken by the organization, and noted that members pay a voluntary contribution of three cents per 100 pounds on their purchases of crude rubber, remitted monthly.

The first office of the Association, Royal Bank Building, 2 King Street East, Toronto. Intersection of King and Yonge streets circa 1930. Photograph taken from the top of the Royal Bank Building. (Credit: City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 10062)

Victor van der Linde of the Van der Linde Rubber Co. expressed the opinion that a distinctly Canadian organization was needed to deal with the specific problems of Canadian manufacturers.

Victor van der Linde of the Van der Linde Rubber Co. expressed the opinion that while he believed the RAA could do a great deal for Canadian manufacturers along general lines, he also believed that a distinctly Canadian organization was needed to deal with the specific problems of Canadian manufacturers such as traffic and transportation situation, export challenges, industrial relations, and the commercial practices of Canadian manufacturers. After further discussion, it was mutually understood that the Canadian organization, whatever its connection with the Rubber Association of America, would have to operate as a distinctly Canadian association.

C.N. Candee presented a motion that the Canadian manufacturers represented at the meeting place themselves on record as desirous of forming an Association. The motion was seconded by Mr. van der Linde and, when put to a vote, was unanimously adopted. Sensing that the group was prepared to move forward quickly, A.D. Thornton moved a motion, duly seconded, to create a temporary Executive Committee to consist of a Chairman, Vice Chairman and five members be appointed to handle the details of forming an organization to be called “The Rubber Association of Canada”.

In quick succession, the group decided to strike a temporary Executive Committee to empower them to apply for a Charter, hire a General Manager, and prepare a draft Constitution and By-laws.

On March 17, 1920, the still-temporary Executive Committee received its Letters Patent, officially incorporating The Rubber Association of Canada.

On April 12, 1920, the provisional Board of Directors met at Goodyear’s offices in Toronto to formally elect its Founding Firm Members:

FOUNDING MEMBER COMPANIES:

Ames Holden McCready Tire Company T.H. Rieder

Canadian Consolidated Rubber Co. A.D. Thornton

Dunlop Tire & Rubber Goods Co. J. Western

Firestone Tire & Rubber Co. of Canada R.H. Jeffers

Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company of Canada Ltd. C.H. Carlisle

Gutta Percha & Rubber Ltd. C.N. Candee

Independent Rubber Co. R.F. Foote

K&S Tire Co. J. O’Mara

Kaufman Rubber A.R. Kaufman

Miner Rubber Company W.H. Miner

Northern Rubber Company A.D. Dwyer

Oak Tire & Rubber Co. F.D. Law

F.E. Partridge Rubber Co. F.E. Partridge

Sterling Rubber Co. F.L. Freudeman

Thornton Rubber Co. J. Thornton

Van der Linde Rubber Co. V. van der Linde

At the same meeting, the members elected their Officers:

Chairman C.H. Carlisle

Vice-Chair J. Thornton

Secretary V. van der Linde

Treasurer C.N. Candee

The Board of Directors also agreed to hire its first General Manager and Secretary, A.B. Hannay at an annual salary of $5,000, payable in equal monthly instalments.

1930s: THE DIRTY THIRTIES

The business conditions in Canadian rubber industry of the 1930s were characterized by high labour costs and difficulty competing with low-cost imports from the U.S. and Hong Kong. The decade became known as the Dirty Thirties due to a crippling drought in the Prairies and Canada’s dependence on both raw materials and farm exports.

Canada was one of the countries most affected by the Great Depression, and the Association felt the full impact of the 1930s in similar fashion as its Members. Due to difficult business conditions, the Board of Directors was also forced to cancel the Annual Meeting Banquet Dinner in 1932, and by 1939 its revenues dropped by 75% from the high watermark of 1927-28.

While operating in economic conditions more severe than those of U.S., the association still made important contributions to its membership on two fronts: It successfully lobbied for a reduction in Excise Tax on crude rubber coming from the British Overseas Territories, which translated into $175,000 of annual savings for the Association’s members. In addition, the Association also lobbied successfully to keep high tariffs on imported finished goods and worked with the Federal Government to improve industry statistics reporting.

Goodyear Blimp over Toronto Bay circa 1930. (Credit: City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244 Item 4552)

1940s: INDUSTRY'S CRITICAL ROLE DURING THE WAR YEARS

Rubber was a critical material in virtually every aspect of wartime manufacturing, and the rubber industry and the Association made great efforts to support the War Effort.

The government deemed rubber so important that the rubber industry was completely coordinated and controlled. Prices were frozen and many products were forbidden so the industry could focus on producing goods designed for war. National War Services promoted the salvaging of rubber on a massive scale and, in 1942, Canada moved to tire rationing for the general public with exemption of essential vehicles.

Women’s participation on the home front was essential to the War Effort. With men fighting overseas, women stepped up to fill vacant positions in essential jobs en masse and excelled in these roles. Work in factories during the war was the most important role played by women on the home front, though the largest overall contribution by the majority of Canadian women was through unpaid volunteer work, where women began collecting recycled items such as rubber, metal, paper, fat, bones, rags, and glass.

Many senior rubber executives were seconded in support of the war. For example, R.A. Martin, Manager of Dominion Rubber Company was appointed Deputy Controller of Rubber Control, a key section within the Department of Munitions and Supply, a post he held from circa 1940 until the unit was disbanded in 1947.

The Association worked very closely with Rubber Control as a liaison between Government and industry to ensure each company received a proper allotment of rubber and produced the necessary goods for both the War Effort and domestic consumption. The government also created a Crown Agency named Fairmont Corporation with the purpose of coordinating the rubber supply into a common pool and acquisition of scrap rubber. Meanwhile, the Department of Munitions and Supply allocated the production of rubber goods for the War Effort not only for Canada’s military but also other members of the coalition. While tires for warplanes, army vehicles, and essential purposes continued to be produced from high quality rubber, scrap rubber was mixed with crude rubber to make items for domestic use.

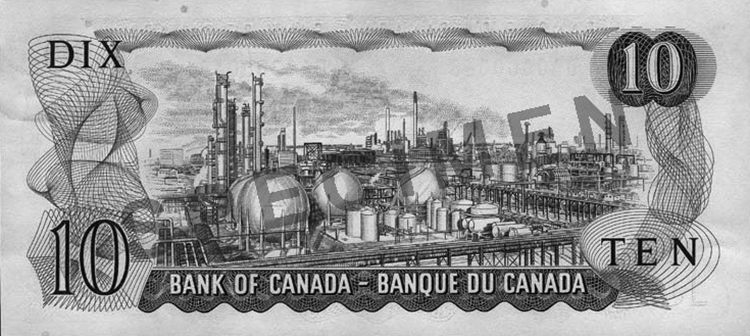

The rubber shortage also led Canada and the United States to establish the Polymer Corporation in 1942, which was tasked to develop synthetic rubber. In February 1944, the company started synthetic rubber production in Sarnia, Ontario, making 3,300 tons of oil-based synthetic rubber per month. The production rendered rubber reclamation unnecessary; however, the demand for synthetic rubber was so great that the company still needed to introduce an allocation program for Canadian manufacturers, a system which remained in place until the 1950s. The company was renamed Polysar in 1976. For its importance in the war effort, the Polymer Corporation plant was featured on the $10 bill between 1971 and 1989.

The Honourable C.D. Howe, Minister of Department of Munitions and Supply sent a letter to the then Chair of the Association, Mr. Paul C. Jones, dated September 12th, 1945. The letter reads:

Dear Mr. Jones: The last order for military tires is virtually complete, and so comes to an end one of the outstanding contributions made by industry to Canada’s War Effort. All tire companies were involved and together they can look back with pride upon the difficulties surmounted in the past six years. From the initial production of run flat tires to the final development of synthetic, each problem as it arose was faced with a will and determination which from the outset insured success. Production of military vehicles has never halted for lack of tires. Essential domestic requirements were always met. Please convey to the staff and workers of all companies mydeep appreciation of what has been accomplished. With kind personal regards, Yours sincerely, C.D. Howe

Workman removes a synthetic rubber tire from the vulcanizing oven at the Dominion Rubber plant. (Credit: Harry Rowed / National Film Board of Canada)

1950s: BLUE SKIES, DARK CLOUDS

In the 1950s, the Canadian rubber industry and economy were in line with high global growth and new investment spurred on by consumer demand for cars, houses, and consumer goods. The suppressed demand for consumer goods in the 1940s meant a boom for the rubber industry and the general economy. The automobile was king, and prospects and opportunities seemed limitless. Then came the Korean War, which led to the North American Defense Production Sharing Agreement. The initiative encouraged the resurgence of Canadian manufacturing from the decline which accompanied the shift and adjustment from global war footing to the peace time of the late 1940s. The government saw the economic boom as a prime time to impose additional taxes on select consumer goods, including vehicles, and tires and tubes.

The Association’s efforts during this period focused on several fronts, notably on lobbying the Government to lower Excise Taxes, securing more favourable freight rates from the railroads and steamship lines, and fighting dumping from low-cost producers such as Czechoslovakia, Norway, and Germany. In his Report to Members (circa 1954) G.B. Smith notes:

“Considerable assistance and support was rendered to Cabot Carbon of Canada Ltd. in establishing freight rates on carbon black from Sarnia, ON, to consuming points in Quebec and Ontario.”

The association also took up the issue of excessive ocean freight rates of Canadian footwear sold to British West Indies. Government took up the issue with Steamship Companies and matters were resolved to industry’s satisfaction.

In a response to 15% Excise Tax on tires and tubes, Association’s General Manager G.B. Smith writes:

“It is an economic absurdity that products which are used mainly in beneficial productive activities should be taxed at the same level as jukeboxes and the like.”

But the dark clouds from the late 1940s rolled in. After a period of hearings – October 1948 to December 1949 – the government charged the Association and many of its members with price fixing under the Combines Investigation Act. The accusation stemmed from the legitimate effort in the mid-1930s and through the war years, when Government bodies imposed price controls on multiple products including rubber goods. During this time, rubber manufacturers were mandated to maintain consistent pricing in order to prevent wartime profiteering. If the Government allowed industry to raise prices, the member companies’ sales managers would meet at the Association, and agree on the price increase and its effective date; and the Association would then send an open letter to all members confirming the price increase. Perhaps out of habit or ease of doing business, the industry continued this practice even after the price controls were lifted after the war.

At the Board meeting in December 1953, the Board agreed to plead guilty to the charge to minimize the cost and reputational damage to the industry. The Association paid a $20,000 fine as did several member companies.

1960s: POLICY, SAFETY, AND EDUCATION

The 1960s saw Canada adopting a new national flag in 1965 and Canadian Centennial celebrations of 1967. This was a decade of Canada making its independent mark on the world. The country worked to define a culture of its own as well as make a name for itself through technological innovation. Some of the notable Canadian technologies born in this era were atomic clock, IMAX Movie System and Canadarm.

Taxes and tariffs continued to represent a significant part of the Association’s mandate and issues of tire standards and safety also started to take the front seat. Prior to the 1960s, no established quality standards existed for passenger car tires at the time, and so the Canadian Standards Association asked the rubber industry to act on this matter. As the RMA created its minimum standards for the U.S. in 1964, the Association took steps to introduce similar guidelines for Canada. The Ontario Ministry of Transport adopted the V-1 Standards into the law and established appropriate enforcement regulations in 1967.

The Canadian Standards Association later adopted the U.S. Federal Standards which would be adopted by four provinces.

Public policy, driving safety, and education also came into focus. The Association worked with the Canadian Highway and Safety Council on promoting highway safety, producing and distributing video clips about safe summer and winter driving, and also sponsoring the Canadian Boy Scouts Association at the Expo 67 held in Montreal.

In this decade, the Association also conducted intensive work on tax and tariff issues. The major work focused on the Automotive Products Trade Agreement of 1965 and the Canada-US Auto Pact, which led to the integration of Canadian and U.S. auto industries into a shared North American market. The safeguards built into the Auto Pact led to a parallel expansion of the rubber manufacturing industry to meet the increased demand for tires, tubes and automotive rubber components.

Statistics and industry reporting remained the key value to the Association’s membership, and encompassed all major market segments (tires, footwear, etc.). Meeting reporting and delivery deadlines always represented a major concern for the Association members to a point where member companies’ presidents would step in if issues or delays occurred.

1970s: TRADE, TARIFFS, AND STANDARDS

Marking its 50th anniversary in 1970, the now highly-respected industry Association continued to build its industry relationships and footprint. Its work included stakeholders such as the Canada Safety Council and Canadian Council of Motor Transportation Administrators (CCMTA). The Association also started to expand its reach internationally by taking up the offer to work with the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). The Association continues to work with all these organizations to this day.

The industry and the government continued to work on creating Canadian tire standards. This topic grew into prominence in the industry during the 1970s, with conversations ranging from manufacturing to on-road safety. One of the main goals for the Association was to create a standard that would encompass the whole federation rather than individual provinces. The Association worked closely with both the CCMTA to create standards that would meet the needs of the Canadians and the RMA to create standards that would work across North America.

The Association has been working with the ISO since it first represented Canada at the plenary session of the Technical Committee 31 (TC31) in 1971. The Association’s current Tire Technical Committee is responsible for development of Canadian tire standards and coordinating its work with the U.S. and the RMA (today’s U.S. Tire Manufacturers Association); and the two organizations had established a subcommittee to keep abreast of the international standards being developed by the ISO.

Due to Canada’s strong market presence in production and development of earthmover tires, the Association also took on a leadership role as the Chair and Secretary of the Subcommittee 6 (SC6, established in 1980) which is responsible for earthmover tire standards. In 1982, Canada hosted its first international meeting of TC31/SC6 in Ottawa and has since hosted delegates from the international tire community on five separate occasions. The Association continues to represent Canada and the industry at the regular TC31 and SC6 international plenary sessions.

Free trade and tariffs remained the main topics the Association tackled in the 1970s as well. Canadian manufacturing continued its struggle to compete in the global markets with higher production and distribution costs, and higher taxes. The rubber industry was seeing low-cost imports and “dumping” in the consumer products category (such as footwear), as well as an influx of competitive tire products from the U.S. and Japan. Facing these challenges, the industry and the government continued the discussion of free trade vs. protectionism. While the tire companies saw tariff reduction as a challenge to the industry, the government was not interested in creating import restrictions or tariff schemes, and rather sought ways to make the Canadian tire and rubber industry more competitive through increased manufacturing productivity.

At the same time, the Canada-US Auto Pact (the Automotive Products Trade Agreement of 1965) continued to grow the Canadian automotive industry. Canada’s share of North American auto production rose from 7.1% in 1965 to 11.2% in 1971 and moved from an automotive industry trade deficit to a modest surplus in 1970.

With the growing variety of tire products, and with winter tires starting to take their rightful place in the Canadian market, the Association also started to conduct winter tire testing.

The industry also saw Michelin opening a tire manufacturing facility in Waterville, Nova Scotia. The facility was built under very favourable conditions and support from the local and federal governments, which ended up creating a rift within the industry and Association membership as other manufacturers sought similar advantages from the government to remain competitive.

For its strategic importance in the war effort, the Polymer Corporation (later Polysar) plant was featured on the $10 bill between 1971 and 1989. (Credit: Bank of Canada)

1980s: COLLAPSE AND RENEWAL

On December 13, 1979, then President of Goodyear Canada, A.W. Dunn wrote a letter to the Association informing them that effective December 31, 1979, Goodyear Canada Inc. and Seiberling Canada Inc. would resign as members. The news was devastating to the organization and quickly raised genuine concern whether the Association could even survive. Not only had Goodyear and Seiberling contributed over a third of the dues, but without Goodyear’s contribution to the tire statistical program, the data was virtually worthless. Goodyear offered the Association a financial lifeline and agreed to pay dues for the first six months of 1980. This allowed the Board time to consider their options. To survive, the Association cut the staff to the barest minimum and installed Doran Moore, former Chairman of Firestone Canada, as the new President of the Association.

The following years saw many overtures by Moore and the Association to Goodyear and Michelin. In 1982, Goodyear rejoined the Association, and the Board approved the membership of Michelin North America (Canada) Inc. Bridgestone and Yokohama joined the Association the same year, and Sumitomo Rubber and Toyo Tire joined in 1983.

On February 8, 1985, Moore, now 72 years of age and satisfied in accomplishing his mandate, turned the reins of the Association over to the former President of Dunlop Canada Ltd., Mr. Brian E. James.

North American Free Trade

In the lead-up to the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement (commonly referred to the CUSFTA) which came into effect on January 1, 1989 (and was superseded by NAFTA in 1994) the Federal Government of Canada and industries questioned whether Canadian manufacturing could compete against U.S. companies without tariffs.

The state of rubber manufacturing in Canada was such that the tire and rubber companies operated mainly smaller, purpose-built factories that served specifically the Canadian market. These smaller production lines with shorter production runs came with higher overheads and general production inefficiencies. At the same time, Industry Canada was interested in maintaining the percentage of Canadian content in automotive production and “Made in Canada” tire fitments on every vehicle was a good way to achieve this goal.

That is why Industry Canada proposed a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) between the Government and the members of the Association to create and participate in a duty remission plan under the Financial Administration Act. The Act allowed rubber companies to claim return of duties paid on imported tires from U.S. in return for new investment in Canada at a three to one ratio, meaning the tire companies received one dollar for every three dollars reinvested in Canada. This duty remission accrued approximately $250 million and the industry invested close to a $1 billion in new tire plants and equipment in Canada. Of course, not all companies were able to take advantage of this plan and, predictably, several Canadian facilities shut down, including Firestone in Hamilton, General Tire in Barrie, and Dunlop in Whitby.

In addition to the MOA, Brian James lobbied for and achieved a 10-year plan for duties phase-out for the tire and rubber industry to help industry prepare for CUSFTA. Thanks to his efforts, the three tire manufacturers operating in Canada – Bridgestone, Goodyear, and Michelin – operate world-class facilities that are fully integrated into their manufacturing operations worldwide. Such is the legacy of Brian James and his successor Don Campbell, both of whom spearheaded the Government’s role in this investment plan.

1990s: GEARING TOWARD SUSTAINABILITY

With massive fires in Hagersville, Ont. and St-Amable, Que., 1990 became the year of the tire fire in Canada. The Hagersville tire fire raged for 17 days in February 1990 and became a daily news feature on national and local TV, newspapers, and radio. This fire came with a final price tag of $10 million just to extinguish, and it is often credited for awakening governments, industry and public for the need to act on discarded tires. The fire became the pivotal moment and remains a continuous reference point that shapes tire recycling, end-of-life management, and tire sustainability efforts in Canada.

At the time, the Association had already created a Scrap Tire Committee to help industry find solutions and to work with provincial governments on funding models to support this effort. In 1989, Ontario instituted a Tire Tax in response to this problem. While the tire tax was ultimately rescinded in 1993, it spurred investment, drew entrepreneurs, ideas, and new technologies toward end-of-life tire management.

In the coming years, many provinces created scrap tire management programs to address this pressing problem. In 1994 the Association created and hosted its first biennial Rubber Recycling Symposium and brought together key industry stakeholders to work together on this serious issue.

Today, each province has a formal, mandated program for managing end-of-life tires. The Association is actively involved in the management of three such programs: British Columbia, Manitoba, and Ontario. Through its relationship with the Canadian Association of Tire Recycling Agencies (CATRA) the Association takes a proactive role in all provincial tire stewardship programs across Canada.

Since the first Rubber Recycling Symposium in 1994, the Association has been conveying the industry’s commitment to a sustainable future.

Three-Peak Mountain Snowflake

In the 1990s, Canada also became the focal point of the global tire industry and policy makers regarding the link between tires and winter driving safety. The issue came under scrutiny as a result of a coroner’s inquest focused on a vehicle collision causing death which was linked directly to the vehicle being equipped with tires not suitable for winter road conditions. The tire industry and policy makers alike recognized the need to classify tires designed for winter driving.

The Association took on the leadership role in creation of global standard with the ASTM F-1805 test method becoming a voluntary, performance-based standard for winter tires. To distinguish the tires that meet this standard the Association also led the development of the Three-Peak Mountain Snowflake (3PMS) symbol. Since 1999, the test and the symbol are used throughout the world to distinguish tires designed for winter driving.

THE ASSOCIATION'S ROLE IN CANADIAN END-OF-LIFE TIRE MANAGEMENT

The saga of tire stewardship in Ontario is much beyond the scope of this commemorative retrospective, though it can be reliably reported that the Association - along with other key stakeholders such as the retailer and independent dealer associations - invested thousands of hours to create a funding and management model that would work for Ontarians and the industry.

Ontario Tire Stewardship (OTS) was created by an agreement amongst its three founding members, the Rubber Association of Canada, Retail Council of Canada and the Ontario Tire Dealers Association, and it received its Letters Patent on September 10, 2003, with its primary objective “to act as an industry funding organization within the meaning of and for the purposes of the Waste Diversion Act (Ontario).” Though primed and ready to take full responsibility for scrap tire management in the province, it would take another six years before the Government produced an enabling regulation to allow OTS to formally begin operations in September 2009.

Over the course of the next decade, OTS made significant contributions to the state of end-of-life tire management in the province, including attracting over $70 million of new processing investments in Ontario, directly investing $6 million in research and development funding, and $20 million in public education campaigns. In addition, though a monopoly, OTS reduced tire stewardship fees over 40% during its 10 years of operation.

Success is no protection from the winds of change and OTS, along with the other industry funding organizations in Ontario, was deemed expendable when Ontario passed the Waste-Free Ontario Act in November 2016. Though OTS would be asked to terminate operations, tire and other waste stream materials’ producers were regulated to take individual responsibility for the goods they supplied to market.

In response, in February 2017 the Association created a federally chartered not-for-profit organization, eTracks Tire Management Systems, to assist tire company members comply with the new regulation. OTS completed its formal wind-up on December 31, 2018 and eTracks began assisting TRAC Members meet their end-of-life tire obligations in January 2019. Though little more than a year old, eTracks is achieving its mandate, demonstrating industry leadership, and offering tangible evidence of TRAC Members’ commitment to tire stewardship—today and tomorrow.

2000s:

In 2001, Bill 90 had received first reading in the Ontario Legislature, thereby creating Waste Diversion Ontario, which in turn would create Industry Funding Organizations for tires, electronics, paints, blue box, etc., and TRAC worked hard to contribute to creation of Ontario Tire Stewardship, which incorporated in 2003. It would take another six years (September 2009) before OTS received regulatory approval. TRAC was also working on launches of Tire Stewardship BC, and Tire Stewardship Manitoba.

TRAC also worked with Transport Canada to better understand NHTSA’s rule-making provisions under new legislation referred to as the TREAD Act—legislation which would consume the tire industry for many years thereafter.

It was also during that time TRAC constructed a Health & Safety Guidebook, published in June 2002 and which became the educational manual to support our Safety Group Program, funded by the Workers Compensation Board and which ultimately returned hundreds of thousands of dollars back to members as rebates.

TRAC launched its Be Tire Smart consumer education campaign.

Nearing the end of the decade, the Great Recession was taking its toll. Key members like Gates and Dayco had mothballed their Canadian facilities, taking valuable allies and volunteers from TRAC membership. A comprehensive membership drive was put in place at the end of the decade which began to bear fruit and take hold over the coming years.

Four Association’s Presidents: From the left, Don Campbell (1997-2001), Doran Moore (1980-1985), Glenn Maidment (2001-2020), Brian James (1985-1997)

2010s:

The final decade of TRAC’s first hundred years was a decade where the industry “woke” to its environmental stewardship and the imperative each member saw as their corporate social responsibility to leave the planet in a better shape for our children’s children. In fact, “corporate sustainability,” while perhaps a buzzword in some sectors, was for the rubber sector a real and important driver of R&D efforts. We began to see major tire manufacturers investing in large end-of-life tire processors and using recycled rubber material in new production. The industry saw an emphasis on substituting petrochemicals with renewable biogenic materials, investments in replacement for natural rubber, and also commitments to natural rubber sustainability. For TRAC, this member focus supported the earlier investments in Rubber Recycling Symposium, which began in 1994, and turned the event into an even more important vehicle for conveying the industry’s commitment to a sustainable future.

TRAC’s work with the provincial tire stewardship programs in Ontario, Manitoba and B.C. parlayed into an important role with the Canadian Association of Tire Recycling Agencies (CATRA) and a long-standing leadership role to guide and nurture Canada’s efforts in responsible tire stewardship. The numbers speak for themselves—Canada’s success in managing end-of-life tires (virtually 100% diversion rates according to CATRAs data) is unparalleled by world standards, and TRAC and its members can deservedly take some credit for it being so.